A super-fit swimmer and lifeguard, Becky Bessell had long looked after herself and had no health problems until her mid-40s, when she started experiencing a cluster of seemingly minor problems, including itchy skin on her back and fatigue.

The GP put these down to perimenopause, prescribing an emollient to moisturise her skin, and hormone replacement therapy (HRT).

‘The HRT helped with my energy levels for a while, but the itching didn’t go away,’ recalls Becky.

‘Then, over the next few years, I seemed to get more and more tired – falling asleep on the sofa by 8.30pm. It wasn’t like me at all, I usually had bags of energy.

‘My fingers were also puffy and I couldn’t get my rings on, which didn’t seem right as I wasn’t overweight – but I didn’t mention this [to the GP] at that stage as they didn’t hurt.’

Then in April last year, her hand and wrist suddenly became very painful.

‘It was difficult for me to type at work and hold equipment in the gym,’ recalls the former sales administrator, who lives in Peasedown St John, Somerset.

So Becky went back to the GP who referred her for further tests. Appointment after appointment followed, first with an orthopaedic surgeon, then with a series of rheumatologists.

Becky Bessell was initially given an emollient to treat her itchy skin as doctors thought she was experiencing perimenopause

Initially, she was diagnosed with psoriatic arthritis by a private doctor – an autoimmune condition – and was prescribed steroids. But when these didn’t help, a private doctor told Becky she didn’t, in fact, have the condition.

‘It was so confusing,’ she recalls. ‘But he promised he would discuss my case at a multi-disciplinary team meeting [with other specialists] to try to get me a correct diagnosis.’

Yet before the meeting could be held, four weeks later, Becky’s condition dramatically worsened, as she began vomiting several times a day.

‘Then I started to swell up – beginning under my eyes and spreading to the rest of my face. I looked like something out of a horror movie,’ she recalls.

‘A friend took one look at me when she came to visit and took me straight to A&E.’

Doctors ran blood tests but sent her home, asking her to see her GP for follow-up.

‘I emailed my GP overnight because I was worried and they called first thing, asking me to come in that day,’ says Becky.

She was then told she had nephrotic syndrome – ‘basically my kidneys had failed and the blood test revealed large amounts of protein were leaking into my blood, causing fluid retention and swelling’, says Becky.

Becky was finally diagnosed with nephrotic syndrome, as large amounts of protein were leaking into her blood

‘I couldn’t believe what I was hearing.’

In fact, experts warn that too many patients are having their kidney disease picked up late, when the damage is irreversible, when simple blood and urine tests can detect it early when it is far more treatable.

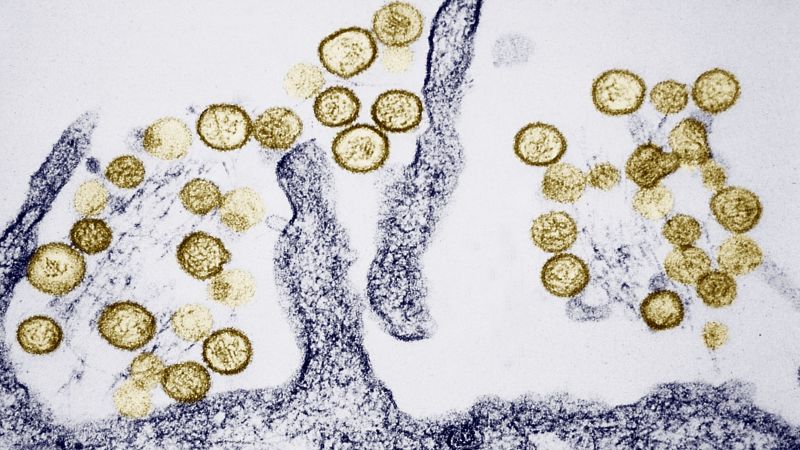

Kidney failure occurs when the kidneys no longer filter out toxins and waste products, and remove water from the blood.

Waste then builds up in the body – the toxins cause itchy skin and fatigue, while excess sodium in the body leads to fluid retention and symptoms such as ankle and facial swelling, as well as breathlessness.

Other symptoms include muscle cramps, weight loss and poor appetite, an increased need to pass urine, nausea, headaches – and in men, erectile dysfunction.

More than 7.2 million people in the UK have chronic kidney disease (CKD), usually a slow, progressive disease caused by an illness such as high blood pressure, diabetes or inflammation in the kidney caused by infections or autoimmune disease.

Around 3.5 million cases are diagnosed at a later stage when symptoms are likely to become increasingly difficult to manage, and the damage is irreversible.

Another 488,000 people have acute kidney injury which causes rapid loss of kidney function due to an event such as dehydration or urinary obstruction. This is reversible if treated in time.

Becky’s creatinine levels were found to be eight times the average, meaning she needed urgent kidney dialysis

As many as one million people in the UK are thought to have undiagnosed kidney disease.

This is due partly to the disease having ‘quite general symptoms’, says Dr Graham Lipkin, a consultant nephrologist at University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, but also simply because people aren’t tested.

Yet these tests – a urine test to detect protein leaking into urine and a blood test to measure creatinine levels, a waste product that indicates kidney function – are extremely quick, easy and cheap to do, and can be done by GPs, explains Dr Lipkin.

‘We know that some people who are at high risk of CKD – for instance, those with high blood pressure, diabetes, or on long-term non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, including aspirin and ibuprofen), are not always having annual tests which could pick it up,’ adds Dr Lipton, who also works at the private HCA Harborne Hospital, Birmingham.

And people are sometimes not being told they are at risk in the first place, says Fiona Loud, policy director at Kidney Care UK.

‘We’ve heard from many people with kidney disease who had previous diagnosis of high blood pressure or diabetes who were never told of their risk of kidney disease,’ she says.

‘Research shows only 29 per cent of people with high blood pressure received urine tests for kidney function in the past year.’

The NHS Health Check (for people aged 40 to 74 without pre-existing health conditions) should help identify people with high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes, which both increase the risk of developing kidney diseases.

While experts aren’t necessarily asking for the simple kidney checks to be added to this NHS health check, we need ‘better follow-up of people with type 2 diabetes or high blood pressure identified in the health check – as these are the two leading causes of kidney disease’, says Fiona Loud.

Still puffy and swollen, on the GP’s advice, Becky drove herself to the hospital where she was prescribed a diuretic (water tablet) to help get rid of some of the fluid – she’d continued to swell at an alarming rate, taking her weight from 52kg (8st 2lb) to 69kg (10st 8lb) over the course of the weekend.

Becky was told she’d be booked in for a kidney biopsy – in six to eight weeks’ time.

Yet within half an hour of getting back home, she started vomiting violently and was brought back in by paramedics.

‘That night was one of the worst of my life,’ says Becky. ‘I literally thought I was going to die.’

A few days later, tests confirmed she was in total kidney failure: her levels of creatinine were eight times the average, and she needed kidney dialysis immediately (where toxins and fluid are filtered out of the blood by a machine).

It’s a scenario far too many people find themselves in, says Dr Lipkin: ‘People often get diagnosed at a late stage. The tragedy is that if CKD is diagnosed early enough there are now newer more effective drugs.’

For example, drugs originally developed for people with type 2 diabetes, called sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors, have been shown to reduce the risk of kidney failure by around a third, according to a review of 13 trials, published in the Lancet in 2022.

Quite why they protect the kidneys isn’t fully understood, but is thought to be linked to their effect on blood vessels.

‘It’s not entirely clear why, but GLP-1 drugs [such as Ozempic and Mounjaro] have also been seen to have a beneficial effect on kidney function,’ adds Dr Lipkin.

This is on top of the existing treatment for earlier-stage kidney disease, including ACE inhibitors to control blood pressure.

Becky spent 23 days in hospital initially – and five months having kidney dialysis for four hours at a time, three times a week. It’s thought the cause in her case is a rare kidney disease, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, which damages the filtration function of the kidneys.

Becky no longer needs dialysis, but takes 16 tablets a day, including immunosuppressants, blood thinners, statins and diuretics. She may have to take these for the rest of her life.

‘My kidney disease has gone into remission with immunosuppressant drugs but it probably won’t ever go away completely.

‘Looking back, there were so many signs that something was wrong with my kidneys,’ says Becky.

‘I ended up on dialysis and think it could have been avoided if I’d been diagnosed back when my symptoms first started, possibly five years earlier.

‘I still wonder, why was a simple urine test not done when I first reported it to my GP?’

You can check your risk at: kidneycareuk.org/kidney-health-checker